From Agave to Bottle: How Tequila Is Made Step by Step

Jimador harvesting Blue Weber agave plants in Jalisco, Mexico — the heart of traditional tequila production.

Tequila isn’t just a spirit poured into shot glasses or mixed into margaritas — it’s Mexico’s cultural gift to the world. Steeped in centuries of tradition, tequila production is a meticulous craft that transforms the humble Blue Weber agave into one of the most celebrated spirits on the planet. From the sun-soaked fields of Jalisco to the copper stills inside artisanal distilleries, every step of the tequila production process carries history, technique, and artistry.

Unlike mass-produced liquors, authentic tequila is bound by strict regulations and cultural heritage. The agave must be grown in specific regions of Mexico, harvested at peak maturity, and carefully transformed through time-honored methods of cooking, fermentation, and distillation. Each stage influences the tequila’s body, aroma, and flavor — making the difference between a harsh shot and a silky, complex spirit worth savoring.

Understanding how tequila is made not only deepens appreciation for what’s in your glass, but also highlights the craftsmanship that separates truly great tequila from the forgettable. In this guide, we’ll explore the artistry behind tequila production, breaking down the key stages — here’s a quick snapshot of the tequila production process:

Harvesting Agave – Skilled jimadores select mature Blue Weber agave plants, ensuring peak sugar content.

Cooking the Piñas – Agave hearts are slow-cooked in traditional hornos or modern autoclaves to convert starches into fermentable sugars.

Fermentation – Cooked agave is mashed and left to ferment, either with natural or cultured yeast, developing the tequila’s character.

Distillation – The fermented liquid is distilled, separating heads, hearts, and tails to refine flavor and alcohol content.

Optional Aging – Depending on the type (reposado, añejo, extra añejo), tequila may be aged in barrels to deepen aroma and complexity.

Harvest: How Agave Becomes the Start of Tequila

Jimador harvesting agave piña with a coa de jima in Jalisco, Mexico — the first step in traditional tequila production.

Every great tequila begins with the Blue Weber agave, a spiky succulent that thrives under the blazing sun of Jalisco. Unlike crops harvested annually, agave requires patience — often taking seven to ten years to reach maturity. In that time, the plant absorbs minerals from the volcanic soil, storing its energy in the heart, or piña, which becomes the raw material for tequila.

Harvesting is not a mechanical process; it is an act of craftsmanship performed by skilled workers known as jimadores. Using a sharp tool called a coa de jima, jimadores carefully trim away the long, spiny leaves to expose the core of the plant. Precision is key: cutting too shallow leaves behind bitter-tasting fibers, while cutting too deep wastes precious sugars.

Timing is everything. A piña harvested too early will lack sufficient sugars for fermentation, while one harvested too late may begin to rot. This is why jimadores are often considered artists in their own right — reading the plant’s size, color, and even the feel of its leaves to determine the perfect moment to harvest.

While some large-scale producers have experimented with mechanized harvesting, most premium tequila still relies on the traditional hand-cut method. The result is not only more respectful to the plant, but also a guarantee that the raw materials entering the tequila-making process are of the highest quality.

As master distiller Carlos Camarena puts it:

“The jimador’s cut is the first step in defining tequila’s flavor. Without care in the field, there is no quality in the bottle.”

In short, the harvest is more than gathering crops — it’s the first act of artistry in tequila production, setting the stage for everything that follows.

Cooking: Unlocking Agave’s Sweetness

Once the piñas are harvested, they must be cooked to unlock their natural sweetness. In their raw state, agave hearts are tough, fibrous, and filled with starches that yeast cannot ferment. Cooking transforms these starches into fermentable sugars, releasing the signature caramelized aromas that hint at the tequila to come.

Agave piñas being slow-cooked in a traditional tequila oven to release natural sugars for fermentation.

Traditional Ovens (Hornos)

The most time-honored method is baking the piñas in stone or brick ovens, known as hornos. This process can take up to 48 hours, followed by another day of slow cooling. The gentle, gradual heat caramelizes the agave, producing rich, honeyed flavors with deep complexity. Many aficionados believe this slow-roasting method creates the most authentic tequila, packed with earthy and smoky undertones.

Autoclaves and Efficiency

Modern producers often turn to autoclaves, large stainless-steel pressure cookers that can complete the cooking process in 12 hours or less. Autoclaves offer efficiency and consistency, making them popular among larger distilleries. However, critics argue that the speed of the process sacrifices some of the depth and nuance found in traditionally cooked agave.

Diffusers: A Controversial Shortcut

Some high-volume tequila operations use diffusers, machines that extract sugars from raw, uncooked agave using hot water and chemicals. While this method drastically reduces production time, it often strips away much of the plant’s natural character. Diffuser-made tequila is widely debated in the industry, with purists dismissing it as an industrial shortcut that prioritizes volume over quality.

Comparing Cooking Methods

| Method | Process Duration | Flavor Profile | Common Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hornos | 36–48 hrs + cooling | Deep, caramelized, earthy, traditional | Premium, artisanal tequilas |

| Autoclaves | 8–12 hrs | Clean, slightly lighter, consistent | Mid- to large-scale producers |

| Diffusers | Hours | Thin, less complexity, industrial | Mass production |

Cooking is one of the most defining choices in tequila production. Whether baked slowly in stone ovens or rushed through stainless steel autoclaves, this step determines how much of the agave’s sweet, complex essence makes it into the fermenter.

Or, as tequila historian Ana María Romero puts it:

“Cooking is not just chemistry. It is where the heart of the agave becomes the heart of tequila.”

Fermentation: The Stage Where Tequila Gets Its Flavor

After the piñas have been carefully cooked and crushed, the sugary juice known as aguamiel is released, sometimes mixed with agave fibers for added depth. This liquid, called the mosto, is the foundation of tequila — and fermentation is where the real transformation begins. It is during this stage that tequila develops its personality, with layers of aromas and flavors that will later be refined in distillation.

At its core, fermentation is the process where yeast consumes sugar and converts it into alcohol. But in tequila production, this step is much more than just science — it’s where the soul of the spirit takes shape. Every decision a producer makes here, from the yeast used to the type of fermentation vessel, influences the eventual taste of the tequila in your glass.

The Role of Yeast

Natural vs. Cultured: The ultimate yeast showdown in tequila production!

One of the most critical decisions is whether to rely on wild, natural yeast or to use cultured yeast strains.

Natural fermentation draws on wild yeast found in the air and environment of the distillery. These native yeasts bring unpredictability and complexity, resulting in tequilas with earthy, layered, and sometimes funky flavor profiles. Each batch may vary slightly, but that uniqueness is precisely what many artisanal producers and tequila enthusiasts celebrate.

Cultured yeast, on the other hand, is carefully selected and introduced by the distiller. It ensures consistency across every batch and offers greater control over the fermentation process. While it often produces a cleaner, lighter flavor profile, critics argue that it can strip away some of the spirit’s individuality.

Both approaches have their place: small-batch distillers often embrace natural yeast for authenticity, while larger producers depend on cultured yeast for stability and predictability.

Time, Vessels, and Conditions

Fermentation can take anywhere from two to seven days, influenced by factors such as temperature, yeast activity, and even altitude. Warmer environments speed up the process, while cooler ones allow for slower, more nuanced flavor development.

Traditional producers often use wooden vats, sometimes made of pine or oak, which can impart subtle characteristics and allow for more interaction with the environment. In contrast, modern operations rely on stainless steel tanks, prized for their cleanliness and precision. While stainless steel offers consistency, it lacks the romantic unpredictability and added flavor nuances that wood can contribute.

The air around the fermenter also plays a role. Distilleries with open-air fermentation, especially in regions with rich microbial ecosystems, may produce tequilas with funky, fruity, or earthy notes that reflect their unique terroir.

Comparing Fermentation Approaches

| Factor | Traditional (Wild Yeast & Wooden Vats) | Modern (Cultured Yeast & Stainless Steel) |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Varies batch to batch | Highly stable and predictable |

| Flavor Profile | Complex, earthy, layered, sometimes funky | Cleaner, lighter, more uniform |

| Fermentation Time | 4–7 days | 2–4 days |

| Influence | Strong sense of place and individuality | Greater control, less environmental impact |

Expert Insight

As tequila educator Tomas Estes once said:

“Fermentation is where tequila’s personality takes shape. Distillation can refine flavors, but it cannot invent them. What happens in the fermenter defines the tequila.”

This idea resonates with many tequila makers: while cooking sets the foundation, fermentation is the creative stage — the point where science, environment, and tradition intersect to give tequila its character.

Why Fermentation Matters

For tequila drinkers, understanding fermentation helps explain why no two bottles taste exactly alike. A tequila fermented with wild yeast in wooden vats may reveal funky, earthy undertones, while one produced with cultured yeast in stainless steel may lean cleaner and brighter. Both are valid expressions of the craft — and both remind us that tequila is not just a drink, but a living reflection of its production choices.

Distillation: Refining Tequila Into Spirit Form

If fermentation gives tequila its character, distillation refines its soul. This stage transforms a murky, beer-like liquid known as mosto muerto (literally, “dead must”) into the clear, potent spirit we recognize as tequila. It’s a step that requires both technical precision and artisanal instinct — because the choices made here determine whether tequila emerges smooth, harsh, or beautifully balanced.

At its core, distillation is the process of heating fermented liquid so that alcohol evaporates and can be collected separately from water and other compounds. But in tequila production, this isn’t just about extracting alcohol — it’s about shaping flavor.

Double Distillation: Tradition and Law

By law, tequila must be distilled at least twice, though some producers distill three times to create ultra-clean spirits. The first distillation, called destrozamiento or “smashing,” takes place in large stills and results in a cloudy liquid with relatively low alcohol content. The second distillation, known as rectificación, refines the spirit further, raising its strength and clarity while concentrating the flavors of cooked agave.

Most tequila hovers between 55% and 60% ABV after distillation, before being diluted with water to the final bottling strength of around 38–40% ABV. This careful reduction is as much an art as the distillation itself — too much water, and the tequila loses its depth; too little, and it risks overpowering the drinker.

Copper Stills vs. Stainless Steel

One of the most important choices in distillation is the material of the still.

Copper pot stills are the hallmark of artisanal production. Copper is a reactive metal that removes unwanted sulfur compounds, resulting in a smoother, more aromatic spirit. Distillers who swear by copper claim it enhances the natural sweetness of agave, giving tequila a fuller body.

Stainless steel stills, often paired with copper coils, are prized in larger operations for their durability and easier maintenance. While they provide efficiency, critics argue that stainless steel lacks the subtle polishing effect of pure copper.

The debate isn’t simply about equipment — it’s about philosophy. For traditionalists, copper represents authenticity, while stainless steel reflects modern scalability. Many distilleries compromise by using stainless steel stills with copper components, aiming to balance efficiency with flavor.

Cuts: Heads, Hearts, and Tails

Perhaps the most delicate part of distillation is the separation of cuts: the heads, hearts, and tails.

Heads: The first vapors to rise contain harsh, volatile compounds like methanol. These are discarded to protect both flavor and safety.

Hearts: This is the prized middle cut, rich with the clean, sweet flavors of cooked agave. It is the essence of tequila, and what distillers strive to capture.

Tails: The last portion of the run contains heavier, oily compounds that can weigh down the spirit. Depending on the style, some distillers blend a small amount of tails back into the final product for added complexity.

Making these cuts isn’t simply a matter of following a timer. It requires a master distiller’s judgment — using sight, smell, and taste to decide exactly where to separate each portion.

Expert Insight

As tequila master distiller Don Felipe Camarena once said:

“Distillation doesn’t create flavor — it reveals it. The choices we make with cuts and stills decide how true the tequila will remain to its agave heart.”

Why Distillation Matters

For the tequila lover, understanding distillation explains why some tequilas feel warm and rustic while others glide across the palate with elegance. Copper vs. stainless, heads vs. hearts — these decisions may seem technical, but they are the finishing touches that transform fermented agave juice into a spirit worthy of its heritage.

Distillation is not just about alcohol. It’s about refining the essence of the agave — ensuring that every bottle carries both the science of purity and the artistry of tradition.

Aging: Developing Depth and Complexity

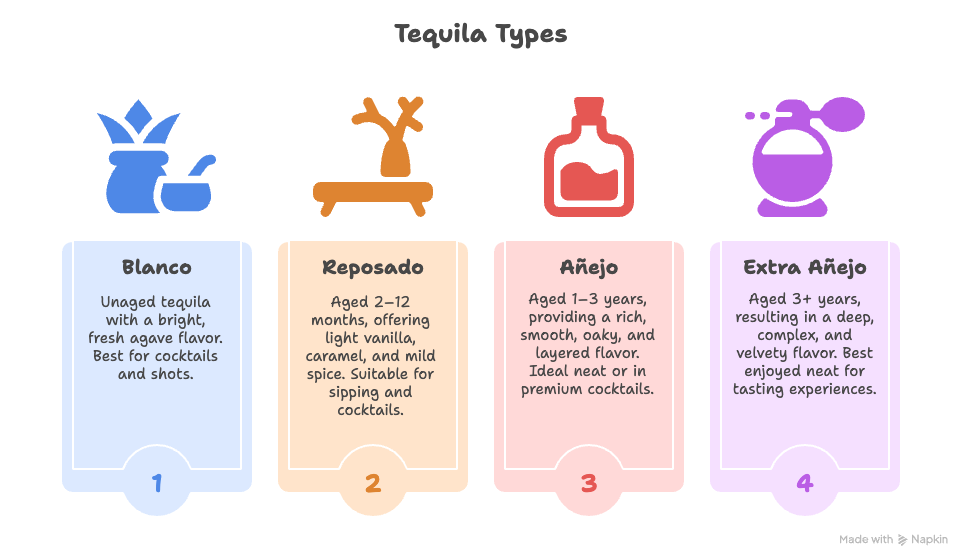

While blanco tequila goes straight from distillation to bottle, many tequilas undergo aging to deepen flavor, color, and aroma. This step is optional, but it plays a pivotal role in shaping the character of the spirit and giving drinkers a more complex tasting experience.

Types of Aged Tequila

Reposado (Rested) – Aged for 2–12 months in oak barrels, reposado tequilas develop subtle vanilla, caramel, and spice notes while maintaining the brightness of the agave.

Añejo (Aged) – Añejo tequilas rest in barrels for 1–3 years, picking up richer flavors, darker hues, and a smoother mouthfeel. These are ideal for sipping neat.

Extra Añejo (Ultra-Aged) – A newer category, aged for over 3 years, extra añejo tequilas boast deep complexity, often rivaling fine whiskies in aroma and richness.

Influence of Barrel Type

The choice of barrel — often oak, sometimes previously used for bourbon or wine — affects how the tequila interacts with wood tannins, sugars, and residual flavors. Artisanal distillers carefully select barrels to balance agave’s natural sweetness with oaky notes, creating a spirit that’s layered, smooth, and memorable.

A few years ago, I toured a distillery in Kentucky that specialized in bourbon, and stacked in their warehouse were rows of oak barrels stamped Hecho en México. The guide explained that once bourbon barrels have been used in the U.S., many are shipped south to Jalisco to age tequila. Seeing that connection firsthand was eye-opening — the same oak that once held sweet, smoky bourbon would later give tequila its vanilla and caramel notes. It was a reminder that while tequila is rooted in Mexican tradition, its aging process often carries a little piece of American history too.

Why Aging Matters

Aging is more than just color change; it is craftsmanship in action. Through careful monitoring and patience, distillers ensure that each batch develops the desired complexity while retaining the spirit’s core agave character. For aficionados, understanding aging elevates every sip, turning tequila tasting into an appreciation of both science and tradition.

From Agave to Glass — The Legacy of Tequila

From the moment an agave plant is planted in Jalisco’s red volcanic soil to the final pour into your glass, tequila tells a story of patience, heritage, and artistry. Each stage of the process — harvesting, cooking, fermenting, distilling, and aging — adds a distinct chapter to the spirit’s character. The result isn’t just a drink, but a cultural symbol that embodies centuries of Mexican tradition and craftsmanship.

For the casual sipper, understanding the tequila-making process transforms every margarita or neat pour into an experience layered with history and skill. For connoisseurs, knowing the nuances between blanco, reposado, and añejo deepens appreciation for how time, technique, and terroir shape flavor.

If you’re curious to explore more, you’ll want to check out our other guides:

Types of Tequila: A Complete Guide — where we break down blancos, reposados, añejos, and more.

From Agave to Icon: The Deep History of Tequila — uncover the rich cultural lineage that dates back over 10,000 years.

FAQs: How Tequila Is Made

-

Tequila is made specifically from Blue Weber agave and can only be produced in designated regions of Mexico, primarily Jalisco. Unlike vodka or rum, which can be made from a variety of grains or sugarcane, tequila’s flavor comes directly from the agave plant. This unique origin gives it earthy, herbal, and sometimes citrusy notes that other spirits can’t replicate.

-

The process begins years before the first bottle is poured. Agave plants must mature for 7–10 years before they’re ready to harvest. After that, production — cooking, fermentation, distillation, and aging (if it’s a reposado, añejo, or extra añejo) — can take anywhere from a few weeks to several years. Blanco tequilas reach the market quickly, while aged tequilas demand patience.

-

Not at all! While many people are introduced to tequila through quick shots with lime and salt, premium tequilas are crafted for sipping. Añejo and extra añejo varieties in particular are best enjoyed neat or over ice, similar to whiskey. Even blancos, with their crisp and vibrant flavors, shine in cocktails beyond margaritas, like palomas or tequila sodas.