The History of Whiskey in Prescott: From Grain to Gold on Whiskey Row

A Tale of Spirit and Saloon

Before Prescott had a courthouse, it had whiskey. And before it was called Whiskey Row, this stretch of rowdy saloons was the lifeblood of Arizona’s frontier spirit—literally. But the story doesn’t start in a bar—it begins in a barrel. Or more accurately, in a grain field.

Whiskey is more than a drink. It’s a distilled legacy of fire, time, and chemistry. It’s also the reason Prescott’s Whiskey Row earned its name—not from some catchy branding, but from the roar of demand that couldn’t be quieted, even by fire (the Great Fire of 1900 leveled the block, and the saloons rebuilt within days).

So how does a humble kernel of grain transform into the golden liquid that built a boomtown?

Let’s pour into the process.

How Whiskey Is Made: Grain to Barrel

Every whiskey story begins here — in the fields of golden grain kissed by the sun.

Grain & Malt Prep: Where It All Begins

Every whiskey starts with grain—usually barley, corn, rye, or wheat. These aren’t just chosen for tradition; each type brings its own signature to the final flavor. But before any grain can become whiskey, it has to be coaxed into giving up its sugars.

This begins with malting: the grain is soaked in water, allowed to sprout just enough to activate natural enzymes, then dried in a kiln. The result is a malted grain ready for conversion—sweet, enzymatically active, and rich in potential.

Next comes milling and mashing. The dried malt is ground into grist and mixed with hot water in a mash tun. This process extracts fermentable sugars, creating a warm, cereal-sweet mash that will soon become the foundation for alcohol.

“Whiskey starts with grain and ends with character—but only if you respect every step in between.”

— Robin Robinson, author of The Complete Whiskey Course

Fermentation: The Yeast Awakens

Fermentation in motion — a 7,500-gallon wooden fermenter turns grain mash into the heart of whiskey.

Once the mash is cooled, it’s time for fermentation. This is where biology takes the wheel.

Yeast is added—often a well-cultured strain known for reliability—and it begins to consume the sugars in the mash. Over the course of two to three days, the yeast converts those sugars into alcohol, producing what’s known as the “wash.” It’s beer-like in alcohol content (around 8–10%) but far from the finished product.

Fermentation doesn’t just generate alcohol—it builds complexity. The byproducts of fermentation, called congeners, are essential to the whiskey’s depth and character. Fruity esters, nutty aldehydes, and spicy phenols all begin here.

In the early days, fermentation vessels might’ve been little more than open wooden tubs, alive with wild yeasts and unpredictable flavors. On Whiskey Row, consistency may not have been guaranteed—but strength and warmth were.

Distillation: Separating the Heart from the Haze

Authentic copper stills inside a working distillery — a behind-the-scenes look at the whiskey-making process.

The wash is now ready for the fire.

In distillation, heat is used to separate alcohol from water and impurities. This happens in a still—traditionally copper—which not only conducts heat efficiently but also reacts with sulfur compounds, smoothing out rough edges in the spirit.

As the wash boils, alcohol vapor rises first. This vapor is collected and condensed into liquid. But not all of it is worth keeping: the distiller carefully cuts the heads (harsh and volatile), isolates the hearts (flavorful and balanced), and discards the tails (oily and bitter).

Prescott’s frontier distillers may not have had lab equipment, but they knew how to judge by smell, taste, and instinct. The art of distillation was passed down like folklore—flawed, fiery, and full of character.

Aging & Maturation: What Time and Oak Can Do

The Angel’s Share has begun.

Freshly distilled whiskey—known as “white dog” or “new make”—is clear, raw, and hot. To become whiskey as we know it, it needs time in the barrel.

Barrels—typically charred American oak—are more than storage. They’re transformational tools. Over the course of at least two to three years, the whiskey absorbs flavors from the wood: vanilla, caramel, spice, and smoke. Meanwhile, oxygen seeps in, mellowing the spirit, while a small percentage evaporates each year—the famous “angel’s share.”

Inside the barrel, three processes take place:

Extraction: the spirit pulls flavor and color from the oak.

Oxidation: chemical changes soften and round the taste.

Evaporation: concentrating what remains into a richer profile.

By the time those barrels made their way to Prescott in the late 1800s—whether shipped in from Kentucky, Missouri, or locally filled—what emerged was more than just a drink. It was a social equalizer, a currency, and eventually, a cornerstone of culture.

Types of American Whiskey Explained

Not All Whiskey Is Created Equal — And That’s the Point

By the time a glass was poured along Prescott’s Whiskey Row in the late 1800s, it likely had already lived several lives — as corn or rye on a dusty Midwestern farm, as steam rising through a copper still, or as a spirit mellowing in oak over years of quiet transformation. But depending on what was in the mash bill or how it was aged, that whiskey would’ve told a different story.

Here’s what sets the major American styles apart.

Bourbon: The American Benchmark

Distillery workers bottling Blanton’s single barrel bourbon by hand at Buffalo Trace Distillery.

Bourbon is to American whiskey what jazz is to American music — bold, homegrown, and legally defined. By law, bourbon must be made in the U.S. from a mash bill that’s at least 51% corn, distilled to no more than 160 proof, and aged in new, charred oak barrels. The high corn content gives bourbon its signature sweetness, while the fresh oak adds layers of vanilla, caramel, and spice.

As whiskey historian Fred Minnick puts it:

“Bourbon isn't just a drink — it's the soul of American whiskey. Those charred oak barrels shape more than flavor; they preserve a heritage.”

(Source: Fred Minnick, Bourbon Authority)

And yes — while Kentucky may get most of the credit today, barrels of bourbon were transported by rail and wagon across the West, including the Arizona Territory, where thirsty miners, travelers, and troublemakers made quick work of them.

Tennessee Whiskey: Bourbon’s Smoother Cousin

At first glance, Tennessee whiskey looks a lot like bourbon. It follows the same general rules — except for one smoky twist: the Lincoln County Process. This filtration step drips the fresh distillate through thick layers of sugar maple charcoal before aging. The result? A smoother sip, with some of the sharp edges softened before the oak even has its say.

Jack Daniel’s, the most famous practitioner of this style, helped define Tennessee whiskey as a distinct and beloved category. Its gentler profile made it a frequent guest in Western saloons — when bartenders could get their hands on it.

Rye Whiskey: The Frontier Favorite

Buffalo Trace Distillery

Before bourbon stole the spotlight, rye whiskey was America’s go-to pour — especially in the Northeast and frontier regions. Made with at least 51% rye grain, this whiskey is bolder, spicier, and more pepper-forward than its corn-heavy cousins.

The lively kick of rye made it perfect for classic cocktails like the Manhattan or Sazerac — and equally well suited to the rowdy energy of Whiskey Row, where nights were long and hangovers legendary.

Wheat Whiskey: Soft Spoken, Underrated

Historic red-trimmed building at Maker’s Mark bourbon distillery.

Less common but still notable is wheat whiskey, made with a majority of wheat in the mash bill. It’s smooth, mellow, and often described as "buttery" — a contrast to rye’s bite or bourbon’s sweetness. Think Maker’s Mark (which uses wheat in place of rye) as a gentle introduction to this style.

How Whiskey Fueled Prescott’s Whiskey Row: The History of Prescott’s Saloons

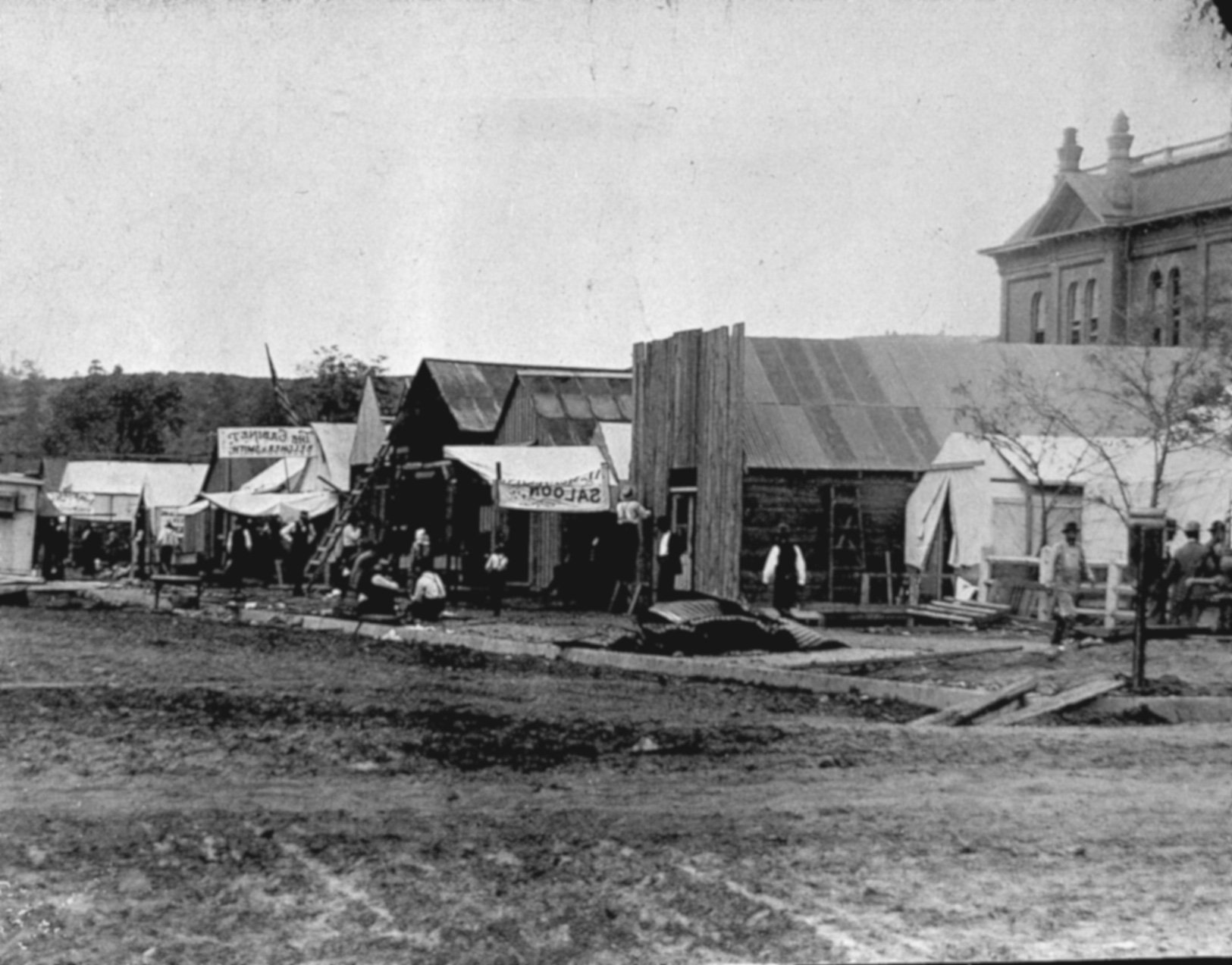

Montezuma Street, Prescott circa 1870 — Whiskey Row before the blaze.

Frontier Currency & Culture

In the rough-and-tumble mining towns of the American West, cash was scarce. Whiskey became more than a drink—it was frontier currency. Miners, cowboys, and prospectors traded labor, supplies, and even land rights for a shot of whiskey. In a place like Prescott, founded in 1864 during the height of the Arizona gold rush, whiskey was as vital as gold itself.

Whiskey was a social glue, too. It marked celebrations and soothed the hard realities of frontier life. The demand from soldiers stationed at Fort Whipple, cattlemen driving herds, and miners digging deep all fueled a booming market. One historian notes, “In these mining camps, whiskey served not just as refreshment but as a key economic medium, lubricating the wheels of an emerging economy” (Source: Arizona Historical Review).

The Rise of Whiskey Row

By the mid-1860s, Montezuma Street in Prescott had transformed from a dusty path into a pulsating artery of saloons. At its peak, the district housed up to 40 saloons, gambling dens, and dance halls lined shoulder-to-shoulder. It became the place where fortunes were won and lost — and legends were born.

The famed Palace Saloon, established in 1877, was a centerpiece, attracting legendary figures like Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday well before their Tombstone fame. These saloons were more than watering holes; they were social institutions where business deals were brokered and community bonds forged.

But Whiskey Row’s wooden buildings were vulnerable. Fires ravaged the area repeatedly — notably in 1877 and again in the devastating 1900 fire that destroyed much of the district. Patrons famously rescued the Palace’s massive cherry-wood bar during the blaze, continuing to drink even as flames engulfed the town. After each fire, Prescott rebuilt with brick and stone, laying the foundation for the Whiskey Row we know today.

Business Behind the Bar

Whiskey Row’s success wasn’t accidental. Entrepreneurs like F. G. McCoy, who opened the Wellington Saloon in 1902, at 136 South Montezuma Street, didn’t just pour drinks; he manufactured them. Local whiskey was decanted into bespoke half-pint and pint bottles stamped with “F. G. McCoy Co., Inc.”—a locally branded spirit line — a savvy marketing move that cemented local loyalty.

F.C. McCoy Stamp

McCoy also leveraged token systems: a 5-cent trade token earned patrons shots, and memberships often included access to back-room gambling dens where poker and faro were daily fixtures.

Even Prohibition couldn’t silence Whiskey Row. When statewide prohibition took effect in 1915, followed by national Prohibition in 1920, saloons adapted by operating as ice cream parlors or soda fountains — fronts that kept the spirit of the Row alive while concealing the flow of whiskey behind closed doors.

For a deeper dive into the colorful characters who defined Whiskey Row, like the entrepreneurial F.G. McCoy and his Wellington Saloon, check out this fantastic historical profile by Pre-Pro Whiskey Men.

Legacy & Today

Prescott’s Whiskey Row: Living History

Whiskey Row’s impact endures. In 1897, it became Prescott’s first street lit with exterior public lighting, inviting night-time revelers to Montezuma Street with glowing neon and lantern light.

Whiskey Row is more than a place; it’s a legacy of resilience, community, and the enduring spirit of the American West — a testament to how whiskey shaped a town, its culture, and its history.

Now, the story continues at Black Vulture Saloon, right here at 144 S Montezuma St, Prescott, AZ. Step inside our doors to experience the same spirit of adventure and community that defined Whiskey Row. Whether you’re savoring a classic whiskey or exploring our unique cocktails, you’re part of a tradition that’s been brewing for over a century.

Come for the history. Stay for the whiskey.

Visit Black Vulture Saloon today — your next great story awaits.

FAQ’s

Does Prescott have any active whiskey distilleries today?

A: While Whiskey Row itself no longer has active whiskey distilleries, Arizona whiskey lovers can enjoy spirits from nearby distilleries like the Granite Mountain Distillery or the Grand Canyon Distillery, which produces authentic Arizona whiskey. Prescott’s Whiskey Row legacy now lives on in its historic saloons rather than production.

What makes Arizona whiskey from Grand Canyon Distillery unique?

A: Arizona whiskey is crafted with a distinctive Southwest influence, often using local grains and pure Arizona water. Grand Canyon Distillery’s whiskey reflects the rugged spirit and natural flavors of the region, making it a must-try for whiskey fans visiting Prescott.

“I love when I’ve never heard of the distillery and go into the tasting experience totally blind… Grand Canyon Bourbon from Canyon Diablo Spirits & Distillery is one such opportunity.”

— Jeff Schwartz (The Whiskeyfellow) on Grand Canyon Bourbon

Can I taste or buy Arizona whiskey in Prescott?

A: Absolutely! Many Prescott bars, including Black Vulture Saloon, feature Arizona whiskey on their menus. Plus, local liquor stores often carry bottles from Grand Canyon Distillery, so you can enjoy a true taste of the Southwest both at the bar and at home.